The stain of racism in football is, you will be unsurprised to learn, not confined to Bulgarian stadia. It’s a serious and unpleasant problem on social media too. To the extent that the noted association footballer Mr. Harold Macguire has been talking about it. According to The Daily Telegraph, "Maguire urged Instagram and Twitter to make users identify themselves in the same way as betting apps after his teammate Paul Pogba was subjected to a torrent of ‘disgusting' racial abuse from anonymous trolls”.

Many other people seem to think that we should do something about this. Following Mr. Macguire’s analysis, the historian Damian Collins MP (chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport select committee in the UK Parliament) said “Account verification should be more widely available and become the norm. I think accounts should be verified, it can’t be right that cowards and racists can hide behind the anonymity of social media to attack people, often using multiple bogus accounts”. This is an interesting observation that jumbles two different issues together: proving the account “David Beckham” points to a specific person, and proving that the specific person it points to is the former Manchester United winger David Beckham. The first is about attaching attributes to a real-world entity, the second about is about the reputation of the real world identity. Thinking these two things through separately is, I think, a key to finding a workable solution to the social media mess, but back to that later.

Another MP, the lawyer Norman Lamb (chair of the Science and Technology select committee) also commented, saying that if social media companies did not act to clean up abuse then the incoming online regulator should take action. It’s not clear to me what he means by “clean up abuse” since it seems implausible that Twitter could monitor billions of messages every day to remove those that cause any offence to anyone (I assume Mr. Lamb doesn’t want them to remove tweets calling for human rights in certain countries, for example).

(In fact it is not at all clear to me what the incoming regulator is going to do at all, but that it is a different matter.)

It’s also not clear to me what MPs and other commentators mean by “bogus accounts”. But from the context, I assume that they mean accounts that cannot be linked to some other identifier that MPs think is a legitimate form of identity, such as the aforementioned passport.

It’s not a new or interesting idea to try to link social media accounts to government-issued identity, as they do in (for example) China. A while back, to pick on one example, the noted entrepreneur Mark Cuban adumbrated Mr. Maguire by saying that "It's time for @twitter to confirm a real name and real person behind every account, and for @facebook to to get far more stringent on the same. I don't care what the user name is. But there needs to be a single human behind every individual account”.

Cuban is as wrong about the real names as Macguire and the MPs are, because anyone familiar with the topic of “real” names knows perfectly well that they make online problems worse rather than better. One example that springs to mind to illustrate this is when the dating platform OKCupid announced it would ask users go by their real names when using its service (the idea was to control harassment and promote community on the platform) but after something of a backlash from the users, they had to relent. Forcing the use of real names in a great many circumstances will mean harassment, abuse and perhaps even worse.

You can understand why. Why on Earth would you want people to know your “real” name? That should be for you to disclose when you want to and to whom you want to. In fact the necessity to present a real name will actually prevent transactions from taking place at all, because the transaction enabler isn’t names, it’s reputations. And pretty basic reputations at that. I think that online dating, frankly, provides a useful way of thinking about the general problem of online identity. In this case, just knowing that the object of your affections is actually a real person and not a bot (remember, in the famous case of the Ashley Madison hack, it turned out that almost all of the women on the site were actually bots) is probably the most important element of the reputational calculus central to online introductions, but after that? Your name? Your social media footprint?

There are plenty of places where I would not want to log in with my “real” name or by using any information that might identify me: the comments section of national newspapers, for example. “Real” names don’t fix any problem because your “real” name is not an identifier, it is just an attribute (refer back to the David Beckham example) and it’s only one of elements that would need to be collected to ascertain the identity of the corresponding real-world legal entity anyway.

What social media needs, and what will help with Mark Cuban’s actual problem with being sure that there is a “single human” behind an account, is the ability to determine whether you are a known real person or not. The problem with bots on social media is just as serious as the problem of racism. Without commenting on the politics of an individual issue, I could have chosen any of a thousand examples to make this point. Here’s just one, from the UK press yesterday: "Almost all of the ten most active Brexit Party supporters on Twitter appear to be automated bots, according to new research".

The way forward is surely not for Twitter et al to try and figure out who is a bot and whether they should be banned (after all, there are plenty of good bots out there) but for Twitter et al to give their users the choice. Why can’t I tell Twitter that I only want to see tweets from real people that can be identified? It’s none of my business who the person actually is and it’s none of Twitter’s business either.

None. Of. Their. Business.

And if you think that I am being excessively privacy-focused (to the point of paranoia) then you are either wrong and don’t read the news or wrong and you do read the news but don’t understand it. My views on the partitioning of identity and reputation, between persona and persona, are founded on a rudimentary knowledge of the real world. I read on the BBC, for example, that a couple Twitter’s ex-employees have been charged in the US with spying!

The charges, unsealed on Wednesday in San Francisco, allege that Saudi agents sought personal information about Twitter users including known critics of the Saudi government.

Ex-Twitter employees accused of spying for Saudi Arabia - BBC News:

Twitter, I read and emphasis, does not to need who you are. Nor do people reading Twitter. Knowing whether @dgwbirch is a real person or not is enough to make social media. Harry Macguire can read my tweets in comfort, knowing that if I commit a criminal offence then the police can go to someone to find out who I am.

But who? Who is that someone who knows whether I am a real person or not and can tell Twitter about it? Working out whether I am a person or not is a difficult problem if you are going to go by reverse Turing tests or Captchas. It’s much easier just to ask someone else who already knows whether I’m a bot or not.

There are plenty of candidates. There’s the Post Office I suppose. And the school. And the doctor. In fact, there are lots of people who could testify to my existence. But the obvious place to start is my bank. So, when I go to sign up for internet dating site, then instead of the dating site trying to work out whether I’m real or not, the dating site can bounce me to my bank (where I can be strongly authenticated using existing infrastructure) and then the bank can send back a token that says “yes this person is real and one of my customers”. It won’t say which customer, of course, because that’s none of the dating site’s business and when the dating site gets hacked it won’t have any customer names or addresses: only tokens. This resolves the Cuban paradox: now you can set your preferences against bots if you want to, but the identity of individuals is protected.

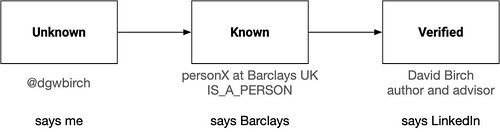

What is crucial here is the IS_A_PERSON attribute. Twitter, for example, should mark my account as of unknown origin until it sees this attribute. Of course, Twitter will want to see it in the form of a verifiable credential signed by someone who they can sue if it turns out I’m not a person after all, but you get the point. When I sign up to Twitter I am “unknown”. When they get a valid IS_A_PERSON credential from me, then my status changes to to “known”. Once I am known, then I can go on to be verified if I want to be.

Most normal people, I imagine, will leave their Twitter account in the default setting of “known only”. Some people might want to go tighter with “verified only”. If nutters want to post racist abuse about footballers, then they will be posting it to each other and the vast majority of us will never be bothered with them again.

(When I last tried to get my account verified at Twitter, they turned me down. They didn’t say why, but presumably they thought that some of my tweets must have been machine-generated or something.)

Look. This is an important issue that I have been posting about for years, to no avail. Anne Marie Slaughter summed the situation up in the FT last year, saying that "with the decline of traditional trusted intermediaries, and the discovery that social media account holders may well be bots, we will crave verifiability”. This is absolutely spot on, and we need to construct the networks capable of delivering this verifiability or we collapse into a dystopian discourse where no-one believes anything. The knee-jerk “present your passport to use Twitter” is not the way forward. Technology means that we can deliver verifiability in a privacy-enhancing manner, so let’s do it.

Comments

Post a Comment