Some people think we are now coming to the end of what economists call the "Bretton Woods II” era of international monetary arrangements and, as The Economist observed recently (“Into the woods”, 17th August), it is not at all clear what is coming next! What will replace the IMF, central banks and commercial banks offering credit when it comes to creating money, facilitating payments and prosperity? The reaction of regulators around the world to one alternative, Facebook’s proposed “Libra” digital currency (more on this later), seems to indicate that the incumbents are not going to give up with out a fight. Yet given the history of financial markets and institutions, and given that we know that change is inevitable as the structures reshape under social, regulatory and technological pressures, it is not good enough to simply say that the incumbents are wrong.

In the financial services world, the view that something radical is happening seems to be gaining ground. Just to give one example, Greg Medcraft, the Chair of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission, said that “traditional” bank current accounts may disappear in the next decade because central banks will create digital currencies and provide payment accounts to customers directly (Australian Financial Review, 3rd September 2017). I have to say, I agree with him on the big picture but I reserve judgement on whether it is central banks or others who will provide the alternatives.

I think that the way that money works now is, essentially, a blip. It’s a temporary institutional arrangement and it must necessity change as technology, business and society change. These sentiments are not restricted to technological determinists of my ilk. As the former governor of the Bank Of England, Mervyn King, wrote in his book The End of Alchemy "although central banks have matured, they have not yet reached old age. But their extinction cannot be ruled out altogether. Societies were managed without central banks in the past". I was reminded of this when I listened to the excellent London FinTech Podcast series produced by my good friend Mike Baliman. In Episode 85 “The Nature of Money, Economic Imbalances & will Central Bank Digital Cash alleviate them?” which Mike made with David Clarke of Positive Money, the idea of central bank digital currency is discussed in some detail. While I understand the reasons why a digital currency is attractive to a central bank (and there are many of them) I’m not convinced that in the long run central banks will retain any sort of monopoly over digital currency. And if they don’t have a monopoly, what can they do to keep the value of their money up and therefore attractive as a store of value?

The 5Cs

I had to think about this sort of thing in some detail when the kind people from Amsterdam Institute of Finance (AIF) and the Dutch central bank (Die Nederlandsche Bank, DNB) invited me to Amsterdam to launch my book "Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin” (now available in a revised paperback edition) in their fair city, so I took the opportunity to run through the “5Cs” model of money issuing from the book and take questions from a very well-informed audience.

One of the points that I made was that technology is no longer a barrier. The idea of the DNB running something like M-PESA but for Dutch residents is hardly far fetched. There are 26 million M-PESA users in Kenya (as of 2Q17) and Facebook can manage a couple of billion accounts, so I’m sure that DNB could download an app from somewhere to run a few million accounts for the Netherlands. There is a middle way though. The central bank could create the digital currency but it could still distribute it through commercial banks. The commercial banks would not be able to create money as they do now (only the central bank would be able to do this) but they would use their existing systems to manage it.

We had a go at this sort of thing a couple of decades ago with Mondex and its ilk in the first attempts to get bank-issued electronic cash into the mass market. Those efforts failed for a number of reasons but primarily because of a lack of acceptance. It was easy to give people cards but hard to give people terminals. That’s all changed now. M-PESA doesn’t use cards and terminals, it uses mobile phones. I’m sure that when future historians write about the evolution of money, they will see that the mobile phone, not the plastic card, was the nail in the coffin of cash. But back to the point, which is… why bother? What if the Chair of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission is right? Why bother with the commercial banks in this context? Now we are clear about the differences between cryptocurrency and a digital currency, let’s review a few of the key issues:

-

A monetary regime with central bank-issued national digital currency (i.e., digital fiat) has never existed anywhere, a major reason being that the technology to make it feasible and resilient has until now not been available. But now technology is available, and we should use it.

-

The monetary aspects of private digital currencies (a competing currency with an exogenous predetermined money supply) may be seen as undesirable from the perspective of policymakers. Also, as I have mentioned before, the phrase “digital currency” is perhaps a regrettable one as it may invite a number of misunderstandings among casual readers.

-

Digital fiat means a central bank granting universal, electronic, 24 x 7, national currency denominated and interest-bearing access to its balance sheet.

-

The cheapest alternative for running such a system would clearly be a fully centralised architecture like M-PESA but there may be other reasons for want to use some form of shared ledger implementation instead (e.g., resilience).

-

A feature of such a shared ledger system is that the entire history of transactions is available to all verifiers and potentially to the public at large in real time. It would therefore provide vastly more data to policymakers including the ability to observe the response of the economy to shock sort of policy changes almost immediately.

Were we to decide to create a new central bank digital currency issued and managed by commercial banks (let’s call it Brit-PESA) now, of course, we wouldn’t use the basic SIM toolkit and SMS technology of M-PESA. We’d use chat bots and AI and biometrics and voice recognition and all that jazz. I don’t think it would that difficult or that complicated: there would be a system shared by the commercial banks with the funds held in a central account.

There’s a very good reason for doing so. Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 605 by John Barrdear and Michael Kumhof, “The macroeconomics of central bank issued digital currencies” says (amongst other things) that "…we find that CBDC issuance of 30% of GDP, against government bonds, could permanently raise GDP by as much as 3%, due to reductions in real interest rates, distortionary taxes, and monetary transaction costs. Countercyclical CBDC price or quantity rules, as a second monetary policy instrument, could substantially improve the central bank’s ability to stabilise the business cycle".

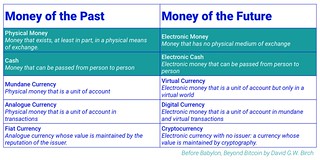

Did you see that? Permanently raise GDP by as much as 3%. Scatchamagowza. Permanently raise GDP by as much as 3%. Why aren’t we doing it right now! Let’s draw a line under the money of the past and focus on the money of the future. Talking of which, back to my presentation at DNB.

Whether digital fiat is the long term future of money or not (and I think it isn’t), let’s get on with it, whether Brit-PESA or Brit-Ledger or Brit-Dex, and give everyone access to payment accounts without credit risk. And there’s another reason, beyond GDP growth, for doing so. Writing in the Bank of England’s “Bank Underground” blog, Simon Scorer from the Digital Currencies Division makes a number of very interesting points about the requirement for some form of digital fiat. He remarks on the transition from dumb money to smart money, and the consequent potential for the implementation of digital fiat to become a platform for innovation (something I strongly agree with), saying that “other possible areas of innovation relate to the potential programmability of payments; for instance, it might be possible to automate some tax payments (e.g. when buying a coffee, the net amount could be paid directly to the coffee shop, with a 20% VAT payment routed directly to HMRC), or parents may be able to set limits on their children’s spending or restrict them to trusted stores or websites".

If digital fiat were to be managed via some form of shared ledger, then Simon’s insight here suggests that it is not the shared ledger but the shared ledger applications (what some people still, annoyingly, insist on calling “smart contracts”) that will become the nexus for radical innovation as they are used to implement new digital currencies.

Why Now?

Now, of course, when techno-determinist mirrorshaded hypester commentators (eg, me) say that the future of money might be somewhat different to that Bretton Woods II structure, and that perhaps the decentralising nature of computer, communications and cryptographic (CCC) together mean that there might be currency issuers other than central banks (as, for example, I did in Wired magazine back in 1995), this might be dismissed by scenario planners and strategists as cypherpunk-addled machinehead-babble.

It seems to me, however, that the reflections of sensible, knowledgable and powerful players is tending intthe same direction. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, recently gave a speech at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in which he said that [Central Banking, 27th August] a form of global digital currency could be "the answer to the destabilising dominance of the US dollar in today’s global monetary system”.

Wow.

The problem that he was alluding to is that the US dollar’s global electronic hegemony "made sense after World War II, when the U.S. accounted for 28% of global exports. Now, the figure is just 8.8%, according to the IMF. Yet the dollar still dominates international trade" [Wall Street Journal, 23rd September]. In his speech Mr. Carney went on to talk about the idea of “synthetic hegemonic currency” (abbreviated to SHC by everyone else but abbreviated to SyHC by me so that I can pronounce it “sick”). An obvious example of such a currency would be an electronic version of the IMF’s Special Drawing Right (SDR). In fact the former boss of SDRs has already put forward such a proposal, asking for the IMF to "develop a procedure for issuing and using market SDRs following currency board rules and backed 100% by official SDRs or by an appropriate mix of sovereign debt of the five basket currencies”.

This, of course, sounds a little like Facebook’s Libra. This came up in historian Niall Ferguson's comment piece on digital currency [Sunday Times, 15th September] where he stated plainly that “if America is smart, it will wake up and start competing for dominance in digital payments”. He argues that a good way to rival Alibaba and Tencent is the aforementioned Libra (although being a nerd, I would say that what he means here is Calibra, the wallet, not Libra the currency). Right now Alipay and WeChat wallets store RMB exchanged in and out bank accounts, but as the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) have made clear in the recent pronouncements, these will soon store the "DC/EP" (digital currency and electronic payment) version, the Chinese digital currency.

So let’s look at the idea of digital currency and then the competing visions of Libra and the DC/EP to form some opinions on the scenarios for the post-Bretton Woods New World Financial System (I couldn’t think of a good acronym, sorry).

Digital and Crypto, Money and Cash

The topic of digital currency is attracting a great deal of (deserved) attention but I find much of the conversation around the subject frustrating. I see commentary that almost randomly switch between “digital currency”, “cryptocurrency” and “digital fiat” to the point that the terms are essentially meaningless. So before we go any further into the subject, I think it might be useful to explore a framework for discussing the topic is a productive way.

Let’s begin by exploring what the central concept is all about. Ben Dyson and Jack Meaning from the Bank of England set out a particular kind of central bank digital currency (what some would call “digital fiat”) with quite specific characteristics. This seems to be to an excellent starting point. They describe a form of digital money that is:

- Universally accessible (anyone can hold it);

- Interest-bearing (with a variable rate of interest);

- Exchangeable for banknotes and central bank reserves at par (i.e. one-for-one);

- Based on accounts linked to real-world identities (not anonymous tokens);

- Withdrawable from your bank accounts (in the same way that you can withdraw banknotes).

This seems to me to be quite sensible definition: central bank digital currency (CBDC) is digital fiat which is one particular kind of digital money. OK. Now, some years ago David Andolfatto, Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, said that it was "hard to see the downsides to central banks supplying digital currency". I agree, although I have long held that central banks will be only one of the providers of digital money and, as we will see, the battle lines are already being drawn up. But how exactly will this digital fiat work?

We have to start to fill in some blanks. For example, should it be centralised, distributed or decentralised? Given that, as The Economist noted in an article about giving access to central bank money to everybody, “administrative costs should be low, given the no-frills nature of the accounts”, and given that a centralised system has the lowest cost, that would seem to point toward something like M-PESA but run by the government.

There are, however, other arguments in favour of using newer and more radical technological solutions, not least of which is our old friend privacy. Again, as The Economist notes, people might well be "uncomfortable with accounts that give governments detailed information about transactions, particularly if they hasten the decline of good old anonymous cash”. However, as I have often written, I think there are ways to deliver appropriate levels of privacy into this kind of transactional system and pseudonymity is an obvious way to do this efficiently within a democratic framework.

So, would such a digital currency be a cryptocurrency? The answer is no, but we might use cryptocurrency to create a digital currency, thanks to the magic of “tokens”. Kevin Werbach published a very good article about these on the Knowledge @ Wharton site. He set out a useful taxonomy, saying that:

- There is cryptocurrency: the idea that networks can securely transfer value without central points of control;

- There is blockchain: the idea that networks can collectively reach consensus about information across trust boundaries;

- And there are cryptoassets: the idea that virtual currencies can be “financialized” into tradable assets.

I might use a slightly different, more generalised approach (because a blockchain is only one kind of shared ledger that could be used to transfer digital values around), but Kevin summarises the situation exceedingly well. His perspective is that cryptocurrency is a revolutionary concept but the jury is still out on whether the revolution will succeed, whereas the shared ledger and the assets that might be managed using those shared ledgers are game-changing innovations but essentially evolutionary. The idea of such assets, which I will label digital bearer instruments, goes back to the long-ago days of DigiCash and Mondex, but the idea of implementing them using technology that is (in principle) available to every single person on the planet is wholly new.

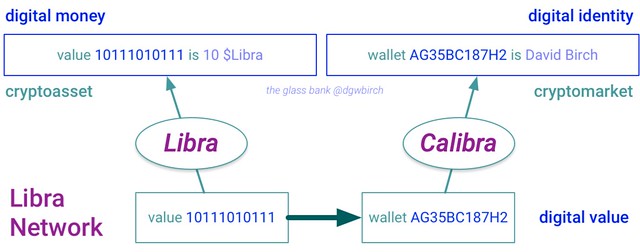

Here’s my take on the situation, then, with a diagram that I’ve used for a while now. We have a value transfer layer that may or may not be implemented using a blockchain, but however constructed makes for the secure transfer of digital values from one storage area (“wallet”) to another. We then a crypto-asset layer built on top of that to link the digital values either to something in the real world—of course, this crypto-asset layer could be null and the digital value itself be the value traded, as in the case of Bitcoin—giving us digital money We then have a crypto-market layer to link the wallets to entities in the real world (eg, people or companies) giving us digital identity.

In this formulation, the digital bearer instruments can be exchanged by “smart contracts” (I prefer the term “consensus applications”). The general term for these bearer assets is “token”, thus I hope you can now see how the world of Bitcoins and tokens and Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) all comes together here. Once digital identities can exchange digital money, we have a functioning base layer for a new financial system based on digital bearer instruments that require no clearing or settlement instead of the existing financial system based on electronic currency, accounts and fiat cash.

Libra and Calibra

A scheme to implement such a base layer has already been put forward by Facebook. And because it is being put forward by Facebook, it is a big deal. A really big deal. As Ed Conway noted in The Times, Mark Zuckerberg once observed that “in a lot of ways, Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company”. Indeed it is, and perhaps it is about to become even more so by planning to have a currency of its own.

The currency is called Libra and the media has been full of commentary about it the new blockchain that will support it (created by the Libra Network) and the new wallets that it will be stored in (created by Calibra, a Facebook subsidiary). Putting to one side whether it is a currency or not or a blockchain or not (Central Banking magazine said that it’s “neither a true currency nor bearing all the hallmarks of a typical crypto asset, Libra will run on a system similar to a blockchain”) and actually I kind of agree with the economist Taylor Nelms that “the crypto angle does seem like a sideshow”, the fact that it exists is nonetheless exceedingly interesting, although not necessarily for reasons that are anything to do with money although it is a payment system of a potentially large scale, as I will explain later.

What is the purpose of this new payment system though? Libra says that hope to offer services such as “paying bills with the push of a button, buying a cup of coffee with the scan of a code or riding your local public transit without needing to carry cash or a metro pass”. But as numerous internet commentators have pointed out, if you live in London or Nairobi or Beijing or Sydney you can already do all of these things. It’s only in San Francisco where such things appear an incredible vision of a future where people don’t write cheques to pay their rent and can ride the bus without a pocket full of quarters.

From a payments perspective it seems a little underwhelming, although I’ve written before that a Facebook payment system would be beneficial and I stand by that. The ability to send money around on the internet is clearly useful and there are all sorts of new products and services that it might support. A currency, however, has more far reaching implications. As J.P. Koenig points out, Libra is more than a means of exchange. The Libra "will be similar to other unit of account baskets like the IMF's special drawing right (SDR), the Asian Monetary Unit (AMU), or the European Currency Unit (ECU), the predecessor to the euro” in that it is a kind of currency board where each of units is a "cocktail" of other currency units. Therefore it is not a digital fiat currency as previously described but nonetheless should, unlike Bitcoin, provide a reasonably stable currency for international trade.

This has significant implications. What if, for example, the inhabitants of some countries abandon their failing inflationary fiat currency and begin to use Libra instead? The ability of central banks to manage the economy would then surely be subverted and this must have political implication. This has not gone unnoticed by the people who understand such things, an example again being Mark Carney, quoted in the Financial Times saying that if Libra does become successful then “it would instantly become systemic and will have to be subject to the highest standards of regulation”. Unsurprisingly, both the international Financial Stability Board and the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority have said they will not allow the world’s largest social network to launch its planned digital currency without "close scrutiny".

Global regulators have responded with varying degrees of scepticism with some jurisdictions (eg, France) saying flat out that they will block it. While the Libra Association remains firm that the system will go live in 2020, many industry observers are already saying that it may never launch in its current forms.

Yes, But...

So there are all kinds of reasons to be sceptical about whether Libra will ever launch and whether it will reach any of the goals set out by its founders. And yet...

There’s something else interesting in Libra. I’ve long written about the inevitability of new technology being used for new payments systems that will in turn be used to create new forms of money. More than two decades ago I wrote about the advent of private currencies and I covered the nature of corporate currencies more recently (and in some detail) in “Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin”.

(Although I have to note that given my “5Cs” taxonomy of the future of money I discussed earlier, I would classify Libra as a community currency rather than a corporate currency, but that’s not the point of this discussion.)

Now, using the model that I set out earlier to help understand what the likely trajectory of digital assets will be, let us looking at the two institutional bindings needed to turn the cryptocurrency technology layer into a new financial system. These are, as noted, the binding of cryptocurrency values to real-world assets and the binding of the wallets to real-word entities. The binding of a wallet address to an actual person is difficult and costly. Here’s what Calibra say about it: "Calibra will ensure compliance with AML/CFT requirements and best practices when it comes to identifying Calibra customers (know your customer [KYC] requirements) by taking the following steps

- Require ID verification (documentary and non-documentary).

- Conduct due diligence on customers commensurate with their risk profile.

- Apply the latest technologies and techniques, such as machine learning, to enhance our KYC and AML/CFT program.

- Report suspicious activity to designated jurisdictional authorities."

I thought it was worth reproducing this in full. So if we put together what the Libra white paper says with what Calibra say about their wallet, you get this specific version of the model. I think it describes the overall proposition quite well.

All well and good. Now, while I was reading through the Libra description, I didn’t find anything remarkable. Until the last part. On page nine of the Libra white paper, just at the very end, I notice that "an additional goal of the association is to develop and promote an open identity standard. We believe that a decentralized and portable digital identity is a prerequisite to financial inclusion and competition".

Well, well. An “open identity standard”.

Identity is at the heart of the proposition, if you ask me. One one first questions that Congress had for the Libra hearing with David Marcus was "how parties will ensure that the user or beneficial owner of a currency or wallet is accurately identified”. Now, you can’t know who the beneficial owner of the currency is any more than you can know who the beneficial owner of a $100 bill is, but you can know who the owner of a wallet is. This question has already been answered, by the way. Kevin Weil, Facebook’s VP of product for Calibra was clear that users will have to "submit government-issued ID to buy Libra” as you would expect. People without IDs will still be able to buy Libra through third-party vendors, of course, but that’s a different point.

Put a pin in “government-issued ID” as we’ll come back to it later.

Its clear that the wallet addresses in a transaction (as shown in my diagram above), a timestamp and the transaction amount will be public because they are on a shared ledger, but as Facebook have made clear, any KYC/AML (ie, the binding shown in my diagram above) will be stored by the wallet providers, including Calibra. Since, as David Marcus has repeatedly pointed out, Libra is open and anyone will be able to connect to the network and create a wallet, there could be many, many wallets. But you’d have to suspect that Facebook’s own Calibra will be in pole position in the race for population scale. Hence Calibra’s approach to identity is really, really, important and Calibra’s global context as a competitor to (for example) Alipay becomes clear.

Now, if Calibra provides a standard way to convert a variety of government-issued IDs into a standard, interoperable ID then that will be of great value. Lots of other people (eg, banks) may well want to use the same standard. In the UK, for example, this would be a way to deliver the new Digital Identity Unit (DIU) goal set out by the Minister for Implementation, Oliver Dowden, of one login for your bank and your pension. But it isn’t only the ID that needs interoperability, it’s the credentials that go with it. This is how your build a reputation economy. Your Calibra wallet can store your IS_OVER_18 credential, your Uber rating and your airline loyalty card in such a way as to make them useful. Now, if you want to register for a dating side, you can log in using Calibra and it will automatically either present the relevant credential or tell you how to get it from a Libra partner (eg, MasterCard).

It seems to me that this may, in time, turn out to be the most important aspect of the "Facebucks" (as I cannot resist calling it) initiative. What if a Calibra wallet turns out to be a crucial asset for many of the world's population not because it contains money but because it contains identity?

Government Issue

Now back to that point about a government-issued ID. One of the other things that governments do is issue passports as a form of formal identity. If I obtain a Calibra wallet by presenting my passport, that’s fine. But suppose I live in a developing country and I have no passport or formal ID of any kind?

Well I think Facebook can make a good argument that your Facebook profile is a more than adequate substitute, especially for the purposes of law enforcement. After all, Facebook knows who I message, my WhatsApp address book, who I hang out with, where I go… Facebook can tell real profiles from fake and they kill off fake “identities” all the time. My guess is that if you have had a Facebook profile for (let’s say) a year, then that identity is more than good enough to be able to open an account to hold Libra up to $10,000 or so and, frankly, it’s beneficial for society as a whole to get those transactions on to an immutable shared ledger.

Frankly, in large part of the world Know-Your-Customer (KYC) could be replaced by Known-bY-Zuck (KYZ) to the great benefit of society as a whole.

Chinese Whispers

Now let us switch attention to what is (in my opinion, and Niall Ferguson’s so far as I can tell) the most important current initiative in the world of digital fiat. This is in China where, of course, fiat currency had its roots when in 1260, Kublai Khan became Emporer and determined that it was a burden to commerce and taxation to have all sorts of currencies in use, ranging from copper ‘cash’ to iron bars, to pearls to salt to specie, so he decided to implement a new currency. Then, as now, a new and growing economy needed a new kind of money to support trade and therefore prosperity. The Khan decided to replace copper, iron, commodity and specie cash with a paper currency. A paper currency! Imagine how crazy that must have sounded! Replacing physical, valuable stuff with bits of paper!

Just as Marco Polo and other medieval travellers returned along the Silk Road breathless with astonishing tales of paper money, so commentators (e.g., me) began tumbling off of flights from Beijing and Shanghai with equally astonishing tales of a land of mobile payments, where paper money is vanishing and consumers pay for everything with smartphones. China is well on the way to becoming a cashless society, with the end of its thousand year experiment with paper money in sight. Already a significant proportion of the population rely wholly on mobile payments and carry no cash at all, much as I do when heading into London.

(In a recent BBC show on the subject, their reporter quotes a rickshaw driving turning down cash in favour of a mobile money transfer as saying “We just don’t use it any more”.)

Now, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is run by smart people and as you might imagine they have been looking at at digital currency strategy to replace cash for some years. It now looks as if Facebook’s Libra initiative has either stimulated or accelerated their tactics. I read in Central Banking [PBoC sounds alarm over Facebook’s Libra] that PBoC officials had "voiced worries" that [Libra] could have destabilising effects on the financial system and further stated that the bank would step up its own efforts to create an e-currency.

This is no knee-jerk reaction. Three years ago the then-Governor of PBoC, Zhou Xiaochuan, very clearly set out their thinking about digital currency, saying that “it is an irresistible trend that paper money will be replaced by new products and new technologies”. He went on to say that as a legal tender, digital currency should be issued by the central bank (my emphasis) and after noting that he thought it would take a decade or so for digital currency to completely replace cash in cash went to state clearly that “he has plans how to gradually phase out paper money”.

(As I have written before, I don’t think a “cashless society” means a society in which notes and coins are outlawed, but a society in which they are irrelevant. Under this definition the PBoC could easily achieve this goal for China.)

What would be the impact of phasing out paper money? Yao Qian, from the PBOC technology department wrote on this subject back in 2017, noting (as I have done) that CBDC would have some consequences for commercial banks, so that it might be better to keep those banks as part of the new monetary arrangement. He described what has been called the “two tier” approach, noting that to offset the shock to the current banking system imposed by an independent digital currency system (and to protect the investment made by commercial banks on infrastructure), it is possible to incorporate digital currency wallet attributes into the existing commercial bank account system "so that electronic currency and digital currency are managed under the same account".

I understand the rationale completely. The Chinese central bank wants the efficiencies that come from having a digital currency but also understands the implications of removing the exorbitant privilege of money creation from the commercial banks. If the commercial banks cannot create money by creating credit, then they can only provide loans from their deposits. Imagine if Bitcoin were the only currency in the world: I’d still need to borrow a few of them to buy a new car, but since Barclays can’t create Bitcoins they can only lend me Bitcoins that they have taken in deposit from other people. Fair enough. But here, as in so many other things, China is a window into the future.

Whether you think CBDC is a good idea or not, you can see that it’s a big step to take and therefore understand the PBoC position. There is a significant potential problem with digital currency created by the central bank. If commercial banks lose deposits and the privilege of creating money, then their functionality and role in the economy is much reduced. We already see this happening because "Alipay, WeChat Wallet, and other Chinese third party payment platforms use financial incentives to encourage users to take money out of their bank accounts and temporarily store it on the platform itself” [China’s Future is Definitely Cashless].

Digital Cash is Different

A couple of year ago I wrote that the PBoC were not going to issue cryptocurrencies and they were not going to issue digital currencies either (at least in the foreseeable future). What I said was that what they might do is to allow commercial banks to create digital currency under central bank control. And this indeed what seems to be happening. According to the South China Morning Post, the new Chinese digital currency "would be centrally controlled by the PBoC, with commercial banks having to hold reserves at the central bank for assets valued in the digital yuan".

How will this work? Well, you could have the central bank provide commercial banks with some sort of cryptographic doodah that would allow them swap electronic money for digital currency under the control of the central bank. Wait a moment, that reminds me of something…

Yep, Mondex again. This “two tier” approach is how Mondex was structured 25 years ago. (If you don’t know what Mondex was, here’s something I wrote about it 20 years on.) There was one big different between Mondex and other electronic money schemes of the time, which was that Mondex would allow offline transfers, chip to chip, without bank (or central bank) intermediation. Would a central bank go for this today? Some form of digital cash that can be passed directly from person to person like Bitcoin rather than some form of electronic money like M-PESA, using hardware rather than proof of work to prevent double spending? Well, it was being tried in Uruguay, where the central bank ran a six month pilot scheme with 10,000 users to test the technology and the concept.

There’s something even more interesting in the PBoC’s plans. When I wrote about this last year, I said that I thought it was unlikely that the PBoC would allow anonymous peer-to-peer transfers, so I was very surprised to see a Reuters report [6th September 2019] quoting Mu Changchun, deputy director of the PBoC’s payments department, saying that the proposed Chinese digital currency would have the ability "to be used without an internet connection would also allow transactions to continue in situations in which communications have broken down, such as an earthquake".

This would seem to mean that the system will allow offline transactions, which means that value can be transferred from one phone to another via local interfaces such as NFC or Bluetooth. If so, this would be truly radical. I wondered if something was mistranslated in the Reuter’s piece so I went to the source speech (albeit via Google Translate!) and I discovered that this is in fact precisely what he said. Talking about the DC/EP tool, he said that it is functionally "exactly the same as paper money, but it is just a digital form” and went on to confirm that "as long as there is a DC/EP digital wallet on the mobile phone, no network is needed, and as long as the two mobile phones touch each other” and, I cannot resist highlighting, went on to say that “even Libra can't do this”.

That's huge. Libra can’t do it, and never will be able to. To understand why, note that there are basically two ways to transfer value between devices and keep the system secure against double-spending. You can do it in hardware (ie, Mondex or the Bank of Canada's Mintchip) or you can do it in software. If you do it in software you either need a central databse (eg DigiCash) or a decentralised alternative (eg, blockchain). But if you use either of these, you need to be online. I don't see how to get the offline functionality without hardware security.

If you do have hardware security and can go offline, then we are back to the question of fungibility again. Here the PBoCs principle is both clear and, to my mind, somewhat surprising. The statement is clear: "the public has the need for anonymous payment, but today's payment tools are closely tied to the traditional bank account system… The central bank's digital currency can solve these problems. It can maintain the attributes and main value characteristics of cash and meet the demands of portability and anonymity".

I cannot resist saying wow again at this point. They are serious. As for how it will work, well DC/EP will indeed implement the “two tier” architecture. Commercial banks will have accounts at the central bank and will buy the digital currency at par. Individuals and businesses will open digital wallets provided by commercial banks or other private companies (ie, Alipay and Tencent). This will, as Libra will, mean scale interoperability. The digital currency in my bank app and my Alipay app and my WeChat app will be freely exchangeable. I must be able to transfer value from my Alipay app to your WeChat app for it to be useful. If PBoC crack this they will be on the way to one of the world’s most efficient electronic payment infrastructures.

(Now you can why I agree with Ferguson's characterisation of the Libra as “not a true blockchain cryptocurrency, but more like a digital currency in the Chinese style”.)

The New Cold War

So what is the fear here? What is the weaponry of the new “Cold War” that Ferguson talks about. I think it is this. If the Alipay and WeChat wallets become widely used by a couple of billion people, starting with the those along the “belt and road” trading corridors, they may well begin by using their own currencies but they will pretty soon shift to the digital Remibi if it does indeed offer speed, convenience and person-to-person transfers. A trader in Africa may soon find it more than a little convenient to order goods from a Chinese partner via WeChat and settle via Alipay. And if they can settle instantly with their Chinese digital currency (or, to be fair, Libra or something similar) then they will soon find themselves accepting the same in payment.

Now it is important to note that this is not necessarily a bad thing for some countries. In a very interesting recent paper on this topic "How Do Private Digital Currencies Affect Government Policy?”, Max Raskin, Fahad Salah and David Yermack highlight "the potential for private digital currencies to improve welfare within an emerging market with a selfish government. In that setting, we demonstrate that a private digital currency not only improves citizen welfare but also encourages local investment and enhances government welfare”. Along the belt and road then, not only might digital currency be acceptable, it might be highly beneficial.

The real fear of some observers, then, is that new Cold War breaks out, with Calibra facing off with Alipay on the one hand but, more importantly, CNY facing off with the USD. That’s a pretty big deal, frankly, because it means that a proportion of the world’s financial transactions stop being dollar denominated and the demand for dollars falls.

(Which, as I understand international economics, might be welcomed by President Trump because he wants a weaker dollar so the political, economic and technical stars may be aligning.)

The digital money debate is no longer about hash tables vs. smart chips or whatever. This is all about global power. Being a historian, it is natural for Mr. Ferguson to remind us that the countries that have forged the path in financial innovation have lead in every other way too. He cites Renaissance Italy, imperial Spain, Dutch republic and the British Empire on to post-1930s America. He then goes on to note that should a country lose that financial leadership, it loses its place as global hegemon. And that has some serious consequences. Whether you think it might be a good thing or not, the dollar’s dominance gives America the ability to use the international payments system as an arms of its foreign policy, as power that, as Ferguson puts it, other countries have found "increasingly irksome”.

Note the real and serious implication of replacing the existing financial infrastructure with the new infrastructure based on digital bearer instruments. No clearing and settlement means no transactions going through the international banking system, and no transactions going through the international banking system means that America’s ability to use deliver soft power through SWIFT disappears.

Never mind Star Wars

It is hardly for me to suggest a defence strategy for the dollar, but in the light of the comments of people far better qualified than I am on the post-Bretton Woods world, I might make a few suggestions.

First of all, digital identity. America (and, for that matter the UK and everywhere else) should take a leaf out of Facebook’s book and create a global digital identity infrastructure for the always-on, connected world. I don’t want to divert into what that might look like (I am, as it happens, writing a book about this!) but suffice to say that, to repeat my mantra, we need a digital identity not digitised identity.

Secondly, digital money. We need a global electronic money licence along the lines of the European Electronic Money Licence (ELMI) with passporting. We need vigorous competition and competitors capable of challenging the incumbents to deliver innovation and we won’t get it if we require companies to obtain banking licences and state money transmitter licences in order to challenge Bank of America or Facebook.

Thirdly, we need to create an alternative to the existing vastly expensive KYC/AML regimes that serve to deliver a defensive moat around the incumbents. We now have a world of AI and machine-learning and, again without diverting, it may work better for the purposes ol law enforcement (and society as a whole) to stop using KYC to create financial exclusion and instead (bearing in mind my suggestions about KYZ!) aim for financial inclusion but use modern technology to track and monitor transactions to look for the criminals and terrorists.

Finally, we need to take Mark Carney’s idea seriously and use the digital identity and digital money platform to create one or more SHCs (and why not start with an eSDR?) that will be globally acceptable and satisfy the demand for an alternative to dollar. If we (ie, the developed nations) don’t do this, and have a seat at the table, then some else will do it and leave us out in the cold.

Comments

Post a Comment