You’ve probably all heard of St. Valentine. He was a third century Roman who helped Christians to escape from prison. He did this by giving them a secret password to give to the guards. But he himself forgot the secret password and when he’d got it wrong for the third time, he was locked in and starved to death. Or something like that, I can’t remember the exact story. Anyway, it’s because of this that St. Valentine became the patron saint of customer verification methods (CVMs).

Now, in ancient times, when European retailers could not go online to verify PINs due to the anticompetitive pricing of the monopoly public telephone providers, it made sense to verify the PIN locally (ie, offline).

This is why, in England, we call 14th February "St. Valetine’s Day” and celebrate the anniversary of the introduction of chip and PIN on 14th February 2006. That special day, often unromantically dubbed “chip and PIN day” by people who do not truly love payments, was the day we stopped pretending that anyone was looking at cardholders’ signatures on the backs of cards and instead mechanised the “computer says no” alternative.

Since then, it has become a tradition to buy flowers using a chip and PIN card and then send them to someone you fancy but not sign the card so that we all remember the end of signatures for transactions.

Sadly, these days, many people do not remember the story of St. Valentine because chip and PIN is on the wane. The majority of card transactions are contactless and have been for some time so we don’t use PINs as much as we used to. And of course more and more of us spend more and more of our money online where we don’t use chips either.

In fact, uncharitable people say that chip and PIN was already out of date when it was introduced in the UK. The truth is, most transactions are authorised online now and would be whether we had chip and PIN or not. The world’s first optimised for offline payment system was launched after the world had already got online. This is why you see smarty pants such as Brian Rommele writing that “by the time the UK implemented chip & PIN, the base concept and much of the technology was already almost 40 years old".

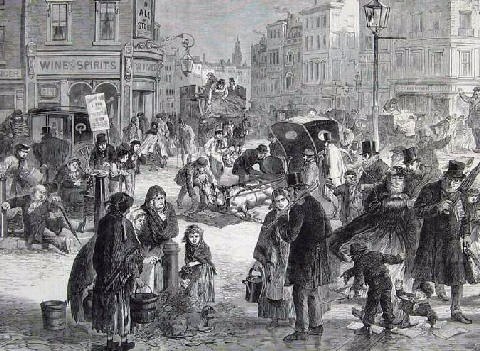

Early chip and PIN focus group.

Annoyingly, it’s hard to argue with Brian about this. When my brand spanking new chip card from a UK issuer not only arrived with a 2010s revision of 2000s app of a 1990s implementation of a 1980s product (debit) on 1970s chip, it also came with a 1960s magnetic stripe on it and a 1950s PAN with a 1940s signature panel on the back. It’s no wonder it seems a little out of place in the modern world.

In 2019 US will discover, as the UK did, that while chip and PIN will put a temporary dent in card fraud, what it will really do is to displace card fraud from card-present to card-not-present channels and fraud will continue to rise. In order to put a lid on fraud, we have to implement two-factor authentication which, in the modern world, generally means the smart phone. So… why not just use the smart phone? Well, this is what is going to happen and it is why I have always insisted that tokenisation is more important than EMV cards.

As I have bored people on Twitter senseless by repeatedly tagging, #appandpay rather than #tapandpay will take us forward.

The retail payment experience will converge across channels to the app and as payments shift in-app so the whole dynamic of the industry will change. Introducing a new payment mechanism faces the well-known “two-sided market” problem: retailers won’t implement the new payment mechanism until lots of consumers use it, consumers won’t use it until they see lots of retailers accepting it. This gives EMV a huge lock-in, since the cost of adding new terminals is too great to justify speculative investment.

When you go in-app, however, the economics change vastly. For Tesco to accept Bitcoin in store is a big investment in terminals, staff training, management and so on. But for the Tesco app to accept Bitcoin is… nothing, really. Just a bit of software. However traditional we might be, the marginal cost of adding new payment mechanisms is falling and our industry needs to think about what that means.

I’m not saying that chip and PIN is going to go away tomorrow, but what I am saying is that it’s time to start thinking about what might come next. Right now, that looks like phone and fingerprint, but who knows what technologies are lurking around to corner to link identification and passive authentication to create an ambient payments environment in which cards (and for the matter, terminals) are present only in a very limited number of use cases.

Comments

Post a Comment